Bitcoin Mining’s Three Body Problem

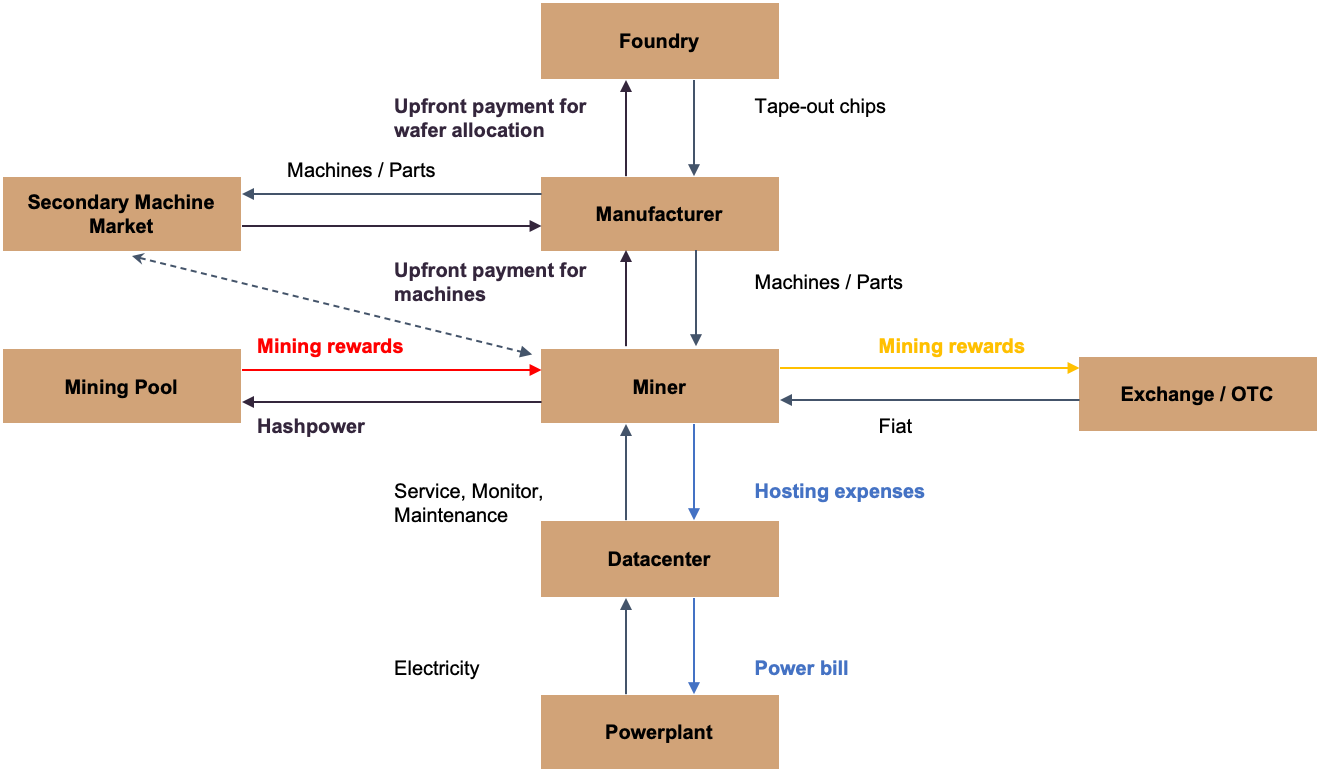

Bitcoin mining is a complex phenomenon that connects hardware and software, the energy and financial markets. Invisible rules govern every aspect of it. The performance of an individual operation is determined by various external factors that are often hard to quantify and almost impossible to forecast.

From a macro perspective, we can identify three principal forces that drive the mining industry as a whole: the emission schedule, the climate cycle, and hardware iteration. Each influences a different component in the miner’s profit calculation:

Mining profit

= Mining Revenue - Mining Expenses

= (Block Reward + Fees) * Price * the Miner’s hashrate / global hashrate - (Electricity Expense + Hardware Depreciation)

The emission schedule drives block reward (revenue).

The climate cycle indirectly drives the industry-average electricity expense (operating expense).

The hardware iteration drives the miner’s hashrate, energy efficiency, as well as hardware depreciation (capital expenditure).

When the first halving occurred in 2012 most people were mining with PCs and GPU rigs at home. Distribution of hashpower was scattered around the world. The dominant force in the market was just the block reward decrease. As the mining cost-of-production doubled, a noticeable amount of hashpower dropped and temporarily switched to the more profitable Litecoin. By the time the second halving took place in 2016, commercial ASICs were already available and industrial mining facilities were put in business.

Long before the third halving transpired in this May, market commentators engaged in heated discussions on possible outcomes. Some echoed that the price will grow exponentially due to the supply shock. Others speculated that 20-30% of the network hashrate would disappear. Because the timing of the halving block overlaps with a transition in the climate cycle and hardware upgrade from 16nm to 8/7nm, all three forces were moving in conjunction.

The Emission Schedule

Bitcoin is the product of hashpower. The industry wouldn’t exist without incentivizing miners to continuously invest in hardware and burning electricity to augment Bitcoin network’s settlement assurance. In absence of a vibrant blockspace market, the block rewards are their primary source of revenue. Over the years, the value of the rewards has significantly grown due to Bitcoin price appreciation, which in turn nurtured the mining business into a billion-dollar industry.

*2020 June-December implied rewards based on 6.25BTC per block and Jan-May price.

(Source: blockchain.info)

Unlike most physical commodities, Bitcoin has a well-defined quadrennial emission reduction schedule mandated by its protocol. Everyday a fixed supply of new coins gets created, and a varying percentage of that gets redistributed to the rest of the Bitcoin economy. Since miners are the only natural suppliers of Bitcoin, and the largest cohort of consistent sellers, profit margin is a key factor in determining the supply side dynamic.

Intuitively, reducing block reward by half immediately doubles every participants’ cost-of-production. Some older generation machines may become too inefficient to operate. Consolidations tend to happen during these times. Miners with access to competitive power sources will purchase these machines in bulk at dirt cheap price, and the machine secondary market becomes far more active.

A miner is a bi-variate call option in physical form. The complexity in pricing and difficulty in transporting goods makes the machine secondary market opaque, illiquid, and highly reliant on insiders. But the poor price discovery at times brings great arbitrage opportunities for resourceful miners. For instance, in late 2018 Bitcoin price experienced a steep decline down to the $3,000 level. A noticeable percentage of the hashpower dropped, spawning a wave of “mining death spiral” headlines. Some miners were able to scoop up large quantities of the Antminer S9s that were temporarily flushed out. In just four months, Bitcoin price propelled into a frenzy bull market. Not only have these buyers made a handsome profit off of the coins they mined, the resale value of the machines also increased by 3x. This demonstrates that unprofitable hardware still have option value.

(Source: proprietary data, courtesy of Jinping Gou)

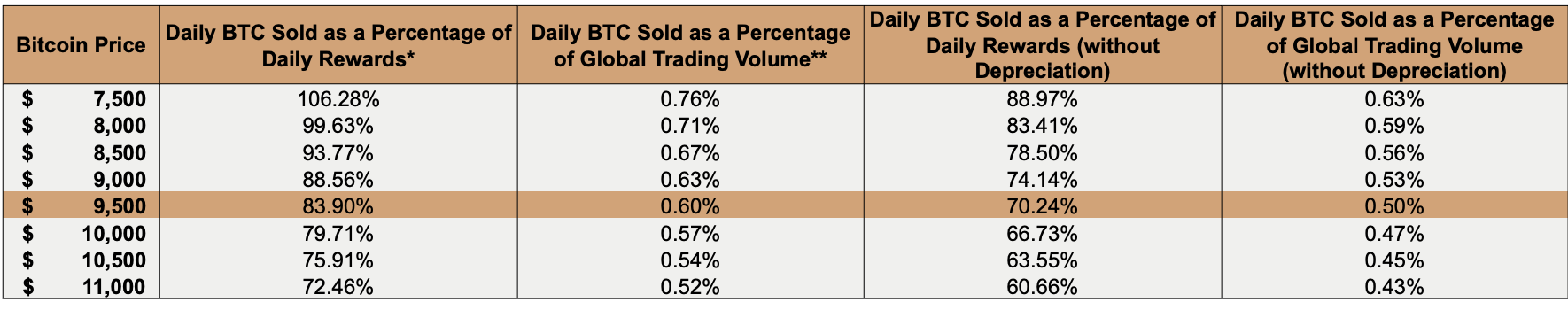

These consolidation activities change the hardware market composition. The market composition tells us how much energy the overall mining activities are consuming. There are a lot of naive attempts at calculating a “price floor” at which miners would stop selling. Every miner’s entry time, amount of capital, cost basis, and risk tolerance is different, hence the industry-wide cost-basis is actually a very wide spectrum. Nonetheless, there will be selling at every level. To assess the entire network’s selling pressure, we need to understand the exact composition of machines. This data is rather challenging to collect since no single party in the industry has access to the entire transaction flow of machines and their energy cost. The Blockware team is one of the latest to try to do this by surveying individual facilities. In the halving opus published in March, they estimate network’s hardware composition as the following:

Post-halving the network hashrate dropped to ~94 EH/s from the ~109 EH/s level in March. Assuming all machines that left the network were the S9s in the bottom categories, we can update the composition table:

*Antminer S9i specs (13.5TH/s, 1,310W) at $21 per unit. Antminer S17+ specs (70TH/s, 2,800W) at $1,232 per unit.

**Linear depreciating over 18 months for S9i, and 36 months for S17+.

Using the data above, we can calculate a rough weighted-average selling pressure at various price levels, as a percentage of the global daily trading volume:

Showing a relatively tight price range since global trading volume changes greatly as price moves.

*6.25 BTC per block. Transaction fees not included.

**Global trading volume of $1.14Bn on Bitwise.

Note that this analysis is for illustrative purposes only. Here all old generation machines are represented by S9 and new generation machines by S17. Needless to say, miners purchase machines from multiple manufacturers, and same generation machines from different manufacturers have very different specs. In reality the variance of market composition is much larger. In addition, this analysis is a static snapshot. Hardware composition is highly fluid, machines are actively switching hands as the market seeks a new post-halving equilibrium. The upcoming flood season in Sichuan also has a drastic impact on a majority of the miners’ electricity cost. As more miners employ financial instruments such as collateralize lending, futures, or even hashpower markets, the network’s miner selling pressure will be partially mitigated or delayed.

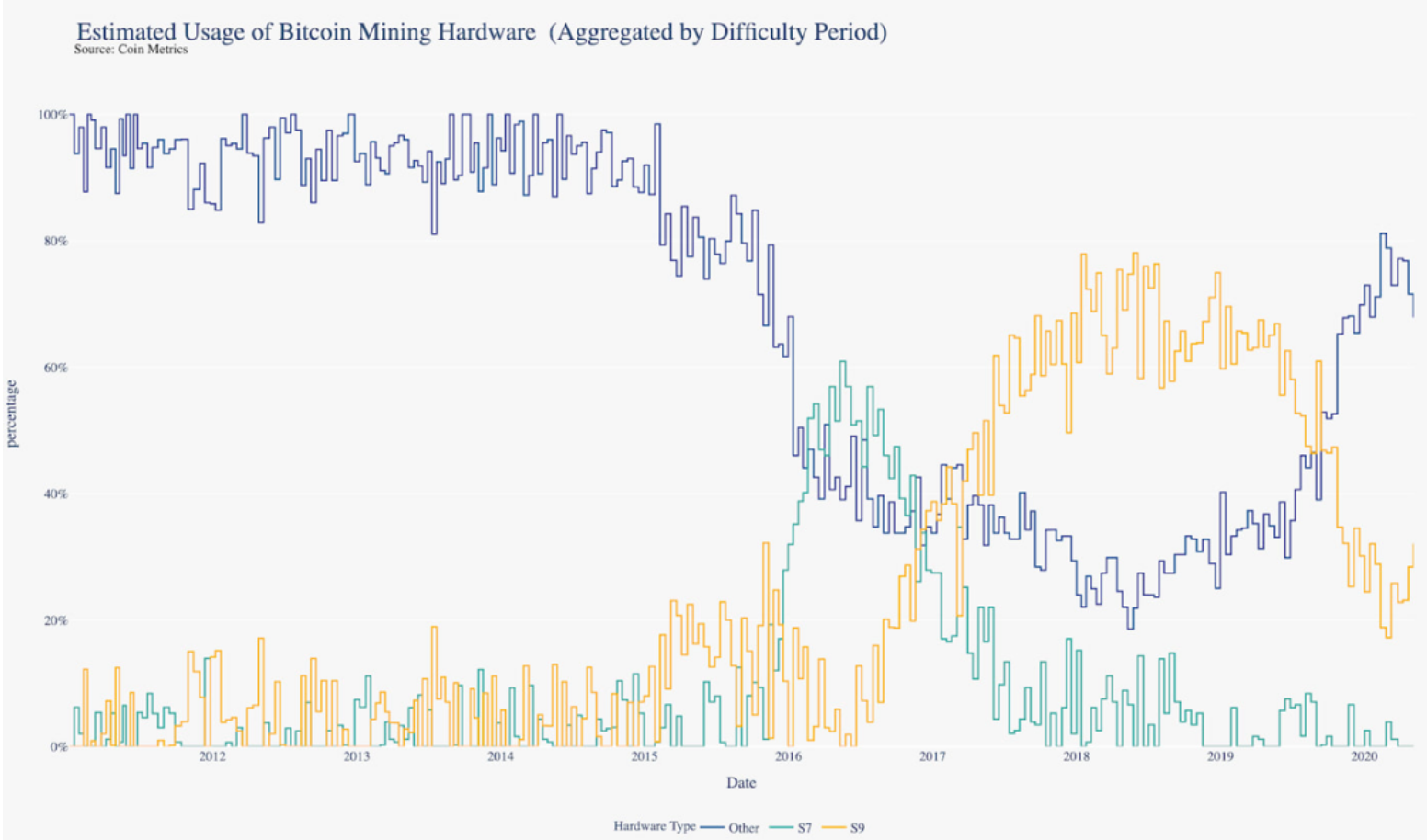

A takeaway from observing how the mining composition evolves over time is that hashpower is "not fungible”, in other word, every unit of hashpower is unique. One TH/s of hashpower today is produced at a different cost-basis from that of yesterday.

The Climate Cycle

The Climate Cycle is the byproduct of the geographical concentration of mining operations. Over the years, the Bitcoin mining industry inadvertently benefited from a massive over-investment in hydropower in southwest China. Excess cheap electricity, massive power capacity, cheap labor cost, and physical proximity to manufacturers make it an ideal location for mining. It is estimated that over 65% of the world's hashpower is concentrated in these provinces.

May-October is the flood season in Southwest China. It is also a festival period for mining businesses as the large supply of surplus hydro capacity significantly cuts down miners’ operating expenses. For small-medium scale miners, the flood season can reduce the cost by as much as 40%. For large miners who own proprietary facilities, the flood season electricity cost is practically negligible. Over 80% of the miners in Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia will migrate in flocks to Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou to take advantage of the discount, and they move back or sell their equipment after the dry season arrives in November.

The thriving mining industry is a boon to the local power plants business. Many converted or constructed their facilities into data centers to host miners.

Example of hosting ads in Sichuan hydropower zone. Rough translation:

“(...)100 MW capacity can start construction immediately (…) Bare electricity 0.15 RMB per KwH, all-in 0.22 RMB per KwH”

(Source: Wechat group)

Gradually, the industry structured itself around these climate patterns. Like ancient rituals, every year before the flood season arrives, major mining conferences get organized in Sichuan’s capital Chengdu. Some facilities are only open to external customers during the flood season. Manufacturers plan their new product release right before it arrives. Miners race to source the latest and greatest machines in bulk.

Hashrate growth during flood seasons:

(Source: coinmetrics.io)

At the beginning of 2020, due to general macro uncertainties, investors and miners reverted to a mode of cautious response. The production of new machines temporarily halted due to supply chain shock from COVID. After the Halving, more machines left the network, leaving the supply of hosting capacity greater than the demand. Many facilities in Sichuan and Yunnan areas are having trouble finding clients. Their desperation further reduces average electricity prices. Compared to last year’s 0.24-0.26 RMB / KwH all-in cost, this year’s average can be as low as 0.10-0.20 RMB / KwH.

The impact from block reward halving will be partially absorbed by the lower power cost. Many facilities had to sign contracts with power plants that promise a minimum usage of electricity. In order to attract business, some of them are offering “joint-mining” programs, where the miners pay de minimis monthly cost, and split the mining revenue with the facility owner. Effectively transferring part of the market risks to the hosts themselves.

However, this doesn’t mean low operating expense is absolutely guaranteed. While hydropower facilities are cheaper during the flood season, they are generally located in extremely remote areas. The power supply and internet connectivity may not be as stable. Sometimes they even risk getting flooded:

Another risk is that local government policies change from time to time. Prior to 2018, most of the local officials had no clue what mining is. The facilities report their activity as data centers for big data or cloud computing projects. In 2018 a committee led by the PBoC dictated cryptocurrency mining as a “false innovation”, citing that mining is extremely wasteful and must “cease in orderly fashion”. Some mining operations did indeed shut down under the pressure. But in late 2019, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) removed mining from a list of activities to be eliminated. Note that the NDRC also oversees the energy industry. Massive amounts of hydropower squandered during flood season is a longstanding issue. The officials are beginning to realize that Bitcoin mining is a highly effective way of transforming excess local capacity into a global digital commodity.

A few months ago, some cities in Sichuan announced a joint-venture program called “Hydropower Consumption Demonstration Zones'' to support the development of the “blockchain industry”. Unfortunately, despite more facilities opened for business, this year’s rain volume hasn’t been as great as expected. At the time of writing, electricity generated by hydropower plants is being transferred to other parts of Sichuan for residential use as the summer heat kicks in.

Last week, a county in Sichuan issued another notice that orders hydro power plants to halt accepting mining businesses. Although insiders on the ground do not expect the order to be enforced, it shows the complexity of the flood season energy scene. It’s not a magic switch that turns on and off to immediately cut down miners’ electricity bills.

The Climate Cycle is a rather unique phenomenon during this stage of cryptocurrency mining. If mining operations migrate to more diverse locations in the future and become less concentrated on a single power source, this cycle will cease to play such a significant role.

Hardware Iteration

Manufacturers are constantly in an arms race to produce the leading product. For a long time Bitmain’s Antminer S9 dominated the market. According to the IPO documents the company filed in 2018, Bitmain machines occupied ~74.5% of the ASICs on the market. But in the past two years, competitors such as MicroBT’s Whatsminer and Canaan’s Avalon are rapidly eating into Bitmain’s market share.

In 2017, Whatsminer sales accounted for ~7.2% of the network hashrate. In 2018, ~9%, and in 2019, ~35%. The shoebox miners are commodity products. While there are qualitative factors that can help a manufacturer standout, such as customer service, delivery time, and supply chain management etc., the competition forces manufacturers to relentlessly focus on two key metrics: unit price and efficiency.

The efficiency is measured by Joule per Th/s. The lower the metrics is, the less energy it consumes to compute a hash function. Each generation of mining hardware is defined by its improvement in efficiency.

*As of May 31th, 2020

**Based on 6.25 BTC block reward, 15,138,043,247,082 difficulty, $9,500 BTC price

Improvement in machine efficiency has a significant impact on earnings. Using the current Bitcoin difficulty, and average price of an used Antminer S9i ($21 per machine, 97.0J per TH/s), we can calculate the approximate days to breakeven at various price levels:

The number of days to breakeven of a new Antminer S19 Pro ($2,407 per machine, 29.5J per TH/s) :

Under most circumstances, S9s are not profitable, but miners with access to extremely cheap power can still operate them at a profit. Comparing the two tables above, we can see at sub $0.04 / KwH, it is faster for the miner to breakeven on S9. Thanks to cheap power sources, machines don’t necessarily retire right away when the new generation hits the market. The team at Coinmetrics put together an estimated usage of Antminer S7 vs. S9 over time based on nonce distribution. As we can see, Antminer S7 usage doesn’t just monotonically decline with the popularization of the S9s:

As discussed in The Emission Schedule section, resourceful miners can strategically take advantage of older generation machines. Such arbitrage opportunities usually appear when hashrate is relatively high and Bitcoin price relatively low. Although the value of hashpower is largely dependent on Bitcoin price, there is a disparity between hashrate and price due to the hardware market’s delayed reaction to movements in the financial market. Manufacturing customized chips incurs non-recurring engineering costs. The miner manufacturer and its supply chain partners amortize expenses over the number of chips manufactured. In many cases the foundry requires the manufacturer to pay in full-upfront for a wafer reserve order, unless the manufacturer is a long-term client with massive orders.

The cycle time of a wafer order is typically 12-13 weeks. The time gap makes it extremely challenging for manufacturers to make forward-thinking business plans. In late 2017, many manufacturers didn't have enough inventory to sell to the market during the bull market, and subsequently misjudged how much longer the market was going to rally. The manufacturers (including Nvidia), over-estimated the amount of orders in 2018, and had to gradually sell inventory at a loss during the second half of the year.

(Source: Bitinfochart)

Once the market finishes upgrading from 16nm to 7nm machines, the backend process arms race will stop for a long time. The average lifetime of the new machines is prolonged from the previous 2 years to 3-4 years. Failure rate of equipment becomes significantly more important. In practice, it will be considered one of the key valuation metrics, along with unit price and efficiency.

Frequent mechanical failures decrease the miner's hash output, and quickly build up the maintenance expense long after warranty ends. High failure means upkeep will eat into a significant % of the revenue. For instance, the Antminer S17 series has a ~30% failure rate due to low quality thermo design. The heat sinks easily collapse on neighboring heat sinks and short-circuit the entire hashing board. This issue is rather expensive to fix, and hence making the S17s a terrible product despite it is based on an advanced backend process.

Advanced machines means higher upfront capital expenditure, which in turn pushes mining to industrialize even more. Soon more data centers will customize their infrastructure to tailor mining-specific requirements. Flare gas mining, immersion cooling, and in-house monitoring solutions are starting to emerge.

In the meantime, should we be concerned that industrialization will further centralize the mining game? Hardware manufacturing is a reproduction process that actively eliminates the need for genetic mutation. At its current state, it benefits from standardization and centralized management. Industrialization is unstoppable in mining. Decentralizing mining is better focused downstream on the distributing ownership of hashpower voting, such as Stratum v2.

After a decade of barbaric growth, the mining industry is at crossroads. The entanglement of the three forces produces unpredictable short-term variances, but over the long-term as Bitcoin integrates deeper and wider with the rest of the economy, mining will become more competitive and resource-intensive. In the past miners only needed to focus on keeping expenses as low as possible. Going forward, the thinning profit margin will force the miners to be more conscious about cash flow and risk management. Two major trends will shape the industry in the future: industrialization and financialization.