The Alchemy of Hashpower, Part I.

July 20, 2020

“Scientific method seeks to understand things as they are, while alchemy seeks to bring about a desired state of affairs. To put it another way, the primary objective of science is truth, that of alchemy, operational success.”

― George Soros, The Alchemy of Finance

The Economic Value of Hashpower

Bitcoin is a new computing paradigm. It abstracts out storage, communication, and computing from dedicated hardware. All nodes perform independent verification of each transaction, new blocks, and selection of the chain with the most computation power. Bitcoin achieves state replication without central coordination. But the design comes with clear trade-offs: in order to give all participants the full copy of the database, redundant messages and data storage are required. The redundancy is inevitable regardless of how much optimization is done to improve on-chain performances. The purpose of this system is not to improve the efficiency over the traditional distributed computation, but to formalize and publicize how the process is done.

Why do we need a computing paradigm that is highly redundant, inefficient, and fully transparent?

In a traditional distributed system, the nodes and their coordination rules are controlled by the institution or the company providing data storage and access services to their business. On the other hand, the Bitcoin network’s consensus and transaction rules are homogeneously obeyed, in spite of the heterogeneity of the nodes. Transactions are sporadically initiated by anonymous participants all over the world with different network speeds. Without a single source of time or an authoritative coordinator, it is impossible to determine at what point in time does a transaction take place. Bitcoin works around the thorny issue of time coordination with proof-of-work, a mechanism that can prove a certain amount of computation resources has been utilized for a period of time. As Gregory Trubeskoy explained, “the difficulty in finding a conforming hash acts as a clock.” Through the ticking of this decentralized clock, the transaction blocks become timestamped, and thus allowing a p2p network to coordinate efficiently. Hashpower crystallizes the sequence of transactions on the ledger, allowing Bitcoin to automate trust, and independently facilitates value transfers and storage with strong assurances.

Settlement assurance is the critical foundation to the adoption and longevity of a settlement network. The settlement assurance, or economic finality, is considered strong when the ordering of the transactions is resistant to tampering. As the blockchain propagates and the network hashpower continues to accumulate, the “energy attached” increases the block’s economic weight. The cost of acquiring 51%+ of the global hashpower may become too expensive compared to the possible gains from launching an attack.

All economic activities flow into the settlement network. In Economics of Bitcoin as a Settlement Network, Saifedean argues that Bitcoin’s ability to handle large settlements compares favorably to those between central banks and financial institutions, thanks to it being cheaper, more verifiable, and free of counterparty risks. The Fedwire system processes over $2 trillion on a daily basis. But only the few chartered banks can benefit from the value accrued from economic activities on top. In Bitcoin, anyone can sustain Bitcoin’s heartbeat by contributing computations, and in return gets rewarded with a share of the economic value. Hashpower secures the Bitcoin network, and the economic value of hashpower in turn is fundamentally driven by the activities on the network. This is how the Bitcoin paradigm connects energy with digital information. This is the Yin-Yang duality of hashpower.

The Hashpower Asset Class

We categorize all assets that produce hashpower in exchange for cryptocurrency, and synthetic contracts / financial instruments that mimic mining returns as part of the hashpower asset class. Despite its short history, investing in this asset class has grown popular. A number of mining special purpose vehicles (SPV), verticalized institutional mining projects, and mining infrastructure / service providers, mining-related financial contracts were launched to satisfy the demand. In this chapter, we describe the key characteristics of different types of hashpower assets, their nature as financial instruments, as well as the challenges each market vector is facing today.

I. The Machine Markets

Unlike the pure digital commodities that they create, a mining operation is significantly affected by physical attributes such as qualities and locations. Producing hashpower involves many exogenous factors such as chips design, tape-out, supply chain, energy source, and maintenance.

New product releases are usually scheduled right before the Sichuan monsoon season to capture miners’ interests, and are usually sold out immediately. Manufacturers would circulate interests from large miners and distributors to anchor the pre-orders, and release only a small percentage online for retail. Latest generation machines are typically available around 6 months after product announcements. Purchasing new machines from manufacturers is similar to purchasing oil term supply contracts before the 1980s. Contracts in which a seller of oil agrees to supply a buyer with specific quantities of oil at scheduled dates in the future, and the price is determined by the oil company unilaterally.

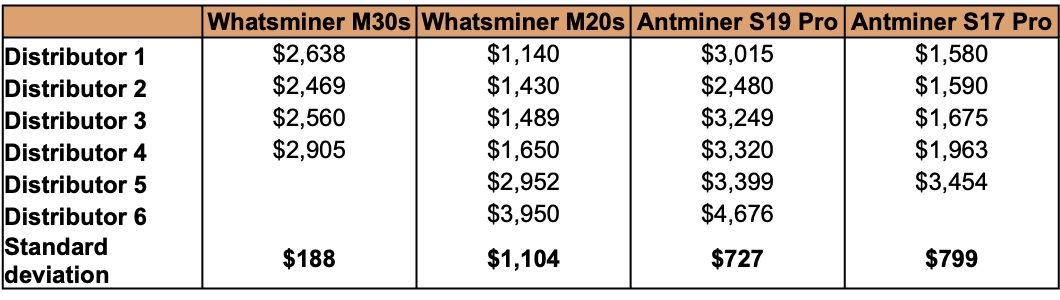

After 2018, manufacturers have become increasingly prudent on inventory management. Manufacturers only assemble machines after orders have been confirmed and aggregated, and buyers typically have to wait 2-3 months for the machines to ship. Since manufacturers only release a fraction to the public, retail buyers often have to acquire miners through distributors and pay an extra premium. The upside is, buyers can get machines sooner if the distributor has the machines in stock. Based on the distributor’s location and inventory availability, the price for the same machine can vary significantly:

(Source:asicminervalue.com)

Used machines also have a rather large secondary market. Trading used machines requires significant experience. Information is highly asymmetric in the secondary market. Transactions are often peer-to-peer, and the sellers have much better understanding of the qualities of the machines than buyers. Used machines are usually way past their warranty. It’s not uncommon for them to underperform expected hashrate. Not to mention some vendors are outright scams. When buying from distributors or secondary markets, it’s important to choose reliable distributors and channels whose reputation is well-established, and sign proper contracts that promise compensation should the machines be delayed, or fail to meet expected performance.

The machine market is notoriously illiquid. Some machines are easier to source via secondary markets because they have been around longer, or produced at greater volume. Mining machines are commodities. Machines with similar efficiency produced by different manufacturers may have similar unit price on manufacturers’ websites. But once they hit the secondary market, it’s all about supply and demand. This is why despite Whatsminer and Canaan rapidly cannibalizing Bitmain’s market share in the past two years, secondary market deals in 2020 so far are still dominated by Bitmain machines:

(Source: Luxor Mining)

II. The Dimensions of Hashpower

There are many factors that influence the pricing of the machines. In this section, we construct a simple proxy model for the valuation of hashpower, and break down how it responds to changes in underlying variables.

The value of hashpower fluctuates as Bitcoin price, network hashpower (technically difficulty, but given that most pools payout calculations are based on expected value, hashrate is good enough as a proxy), and transaction fees change. Using the rigs data on Hashrateindex, we can compare how historical machine prices moved against these variables:

(Data source: Hashrateindex, Coinmetrics)

(S19 and M30 are excluded due to relatively short history.)

Unsurprisingly, machine prices track unit mining revenue the closest. But it doesn’t help us understand the expenses associated with running the hashpower. In the market today, the vogue of hashpower valuation metrics is static days-to-breakeven, especially among the Chinese mining community. It is simple to calculate and intuitive to understand. Similar to how “implied volatility” is the proxy for options valuation, days-to-breakeven has become a popular proxy for machines valuation:

Where:

D is the static days-to-breakeven

C is the upfront capital expenditure

P is the current Bitcoin price

S is hashrate produced by the purchased equipments

H is the network hashrate

m is the coinbase reward, currently it is 6.25BTC.

n is the current avg. transaction fee per block

k is the efficiency (J/T) of the equipments

r is the all-in electricity cost ($/KwH)

Backtest of Days-to-Breakeven of a S17 at various r (all-in electricity cost):

This is a static measure and fails to capture the options value of the machine as the underlyings variables change. There are two main components to this metric: the revenue and the cost. Before making a mining investment, most miners understand their cost structure (hopefully). The unit costs are fixed during the lifetime of the machines (hopefully!). The revenue on the other hand, is determined by three random walks:

We can examine the sensitivity of days-to-breakeven metric by taking its partial derivatives with respect to each variable. This is analogous to options delta, which measures how much the value of the option changes when the underlying asset’s price changes. The higher the absolute number of the output is, the faster days-to-breakeven responds to price change. Sensitivity to price change:

Using the formula above, we can plot out the metric’s sensitivity to BTC price:

The graph shows that as the Bitcoin price increases, days-to-breakeven will gradually become more sensitive to price change. With S9’s sensitivity picking up much faster than the other two. Note that price, network hashpower, and fees are interconnected. But without the explicit function of dH(p) / dp or df(p) / dp, we assume the variables are independent. The same analysis can be applied to network hashpower change:

Sensitivity to network hashpower change:

Next we show sensitivity to average fees per block with different coinbase rewards. As the coinbase reward programmatically reduces, transaction fee plays a more important role as a source of mining revenue. Sensitivity for S19 Pro:

While days-to-breakeven is a simple and intuitive static measure of mining performance, it eliminates the inherent options value of the machines, and thus the metric itself is highly volatile. In order to create a rigorous valuation model for hashpower, we need to capture future uncertainties by treating it as a multivariate option, or synthesize it with a basket of different instruments. These valuation approaches have different pros and cons. We intend to cover these trade-offs and explain the mathematics of each methodologies in a future article on the architecture of a hashpower marketplace. Separately, we will go over other “hashpower greeks” such as gamma (second derivative, the sensitivity of the sensitivities) and theta (time decay).

III. Synthetic Hashpower

In addition to the complexity in financial valuation, purchasing and running mining machines come with many operational challenges. For retail buyers, this process can be daunting to manage. An easier way to get mining exposure is through purchasing cloud mining contracts. Cloud mining is a primitive form of a hashpower financial derivative that separates future production from its current physical location. In this section, we present several different variations of synthetic hashpower.

Over the years, countless cloud mining projects have sprung into existence and quietly faded into oblivion. The dilemma of cloud mining is that it clearly targets retail buyers since large miners are better off operating machines themselves. But evaluating these contracts requires significant insider knowledge about the mining industry, and expertise in complex options pricing. This is a main reason that, despite that in theory, the concept represents a natural next step in developing capital markets, the majority of the current cloud mining projects are considered as “scams” (a lot of them actually are scams).

As an immature and still relatively small field, the cloud mining market suffers from a complete lack of market standards. HoneyLemon Market is a fantastic data aggregator for cloud mining information. Using its dashboard, we can see that different platforms have wildly inconsistent contract terms and pricings:

Currently most of the contracts are unprofitable. Due to the built-in premium on cost-of-production, it requires very specific market conditions in order to generate profits through cloud mining. Typically after a prolonged period of downmarket, and price trend starts to reverse into a natural rally (e.g. April-May of 2019). The demand for hashpower suddenly increases. Purchasing and installing machines may take too long, so buying cloud mining contracts becomes a faster way to build a position. Through cloud mining, investors can also gain exposure to newly launched projects that are not yet available on exchanges. Whats more, hackers can rent hashrate to opportunistically carry out 51% attacks on smaller networks. This is the hashpower Darwinism that filters out poorly designed PoW projects.

Another synthetic hashpower asset is the machine token. They are liquid tokens that represent a fraction of a mining machine. Traders speculate on the secondary market volatility of the machines rather than the coins that they produce. While the concept has been around for a while, volume hasn’t really shown much growth. Mostly because the multivariate nature of mining revenue makes it challenging for speculators to form consensus on pricing “liquid machines”.

Sophisticated traders can structure synthetic hashpower asset portfolios. For instance, a long cloud mining contract can be purchased concurrently with a long position in FTX’s implied hashrate futures, and add a short position on BTC spot futures. There are multiple creative ways to structure mining portfolios with financial instruments. For funds and trading firms who don’t want to own and operate hardwares, this is a cleaner way to gain mining exposure.

Illustrative portfolio:

(Depending on the magnitude of the movements, “long cloud mining contract” is most likely not neutral when Price and Difficulty move in opposite directions. )

In practice, structuring such a portfolio is a highly nuanced task. As the set of days-to-breakeven sensitivity analysis shows, mining metrics’ sensitivities change rapidly as the market evolves. The hedge ratios of each instrument need to constantly be refreshed. Managing it requires close monitoring and making frequent adjustments. However, there are lots of restraints such as poor liquidity and pricing obscurity. Traders need to understand exactly what kind of slippage and discount factors they need to take into risk calculations. By structuring a virtualized hashpower portfolio instead of running a mining operation, the investor effectively exchanges mining operational risks with additional financial risks.

As for miners, a new way to hedge their exposure is through hashpower forwards. Similar to renting hashpower on cloud mining platforms, forward contracts let the miner sell a fixed amount of hashpower for a period of time, for an upfront price. Unlike cloud mining, they are usually structured over-the-counter, and have higher customization flexibility. However, without a public benchmark, the forward market doesn’t have any established pricing framework. Every deal turns into a negotiation, and the desk that execute the trade inevitably has to take on some market risks. A recent high-profile success is the BitOoda transaction with CoinMint, a large mining operation based in New York.

These deals will happen more frequently as more exchanges / financial services vertically integrate with mining pools. Mining pools are excellent aggregators of miners traffic, but after years of development they have turned into commodity software. Everyone wants miners’ trading flow. The deep liquidity reserve of the exchanges allows them to offer creative and potentially risky transaction types to win over miners’ trading flow. Miners can set parameters to always sell a percentage of their hashpower to lock-in the payment for operating expenses, and the counterparty receives the stream of coins produced by that hashpower from the pool. For instance, the miner can pre-sell 100Th/s for 30 days at the beginning of the month. Based on estimated difficulty growth and fees assumptions, the pool offers to pay 0.02 BTC upfront. The miner locks in production of the 100Th/s for the entire month, effectively transferring production risks to the pool.

(Numbers are for illustrative purpose only)

Binance, OK, and Huobi are aggressively expanding their pool business to capture this market share. We expect to see other top exchanges to follow suit, or partner up with existing pool operators very soon. Besides exchanges, some lending firms and trading companies are also venturing in this direction: Babel Finance announced their Ethereum mining pool, Three Arrows Capital will offer structured products through Poolin. In the past, different layers of the cryptocurrency industry have been highly fragmented. Years of trials-and-errors standardizes and commoditizes key infrastructure layers. Some of these standalone infrastructures don’t have defensible business models. Consolidation or verticalization is inevitable.

IV. Hashpower Investment Vehicles

Investing in mining is a full-time job. Most traditional investors and venture capitals don’t have the bandwidth or the expertise to run machines or structure complex virtualized hashpower portfolios. It’s more common for them to get exposure to mining through mining SPV or mining companies. 2019 started with an explosion of overhyped GPU-launched projects. Rumors about deep-pocketed VCs investing hundreds of millions in Grin spread like wildfire. GPU farms that had bitten dust in the last quarter of 2018 were resurrected to ride the wave. Investors wanted to build large positions but did not have the manpower or technical expertise to run machines, causing them to pool capital together to fund mining operations. Managers of the SPVs source and run machines with the investors’ initial investments, and in exchange take a percentage of the mining revenue.

Investing in mining companies is also common for large BTC operations. Some of them are already publicly traded. Mining companies generate bulks of coins every day. A mining operation is effective both as a hardware operator and a liquid fund manager. There are numerous well-capitalized mining projects that failed due to mismanagement of trading positions. A notorious example is Gigawatt in 2018. According to the court case documents, the company had “estimated assets worth less than $50,000, whereas estimated liabilities are in the range of $10–50 million.” by the time it declared bankruptcy.

How the operators manage cash flow is imperative. Developing a reasonable selling strategy to counter changes in market conditions is critical to the fund / company’s financial success. Here we illustrate the backtesting outcomes of four typical strategies:

Assumptions

Starting date: 1/1/2019

Valuation date: 7/1/2020

Initial investment: $1,000,000

Number of machines: 4840 units of S9s, purchased at $206.6 per unit. Linearly depreciating over 18 months.

Total hashpower: 67,761 Th/s

Total power consumption: 6,389KW

All-in rate: $0.04 / KwH

The strategies illustrated above represent different risk preferences for BTC vs. USD positions. Note that in a different market environment, the strategy that yields highest return may be the least profitable. Some miners prefer to hodl regardless of the market conditions until they absolutely have to sell. Depending on the manager’s objective (accumulate BTC or chase USD return), the strategy should be adjusted accordingly. Mining operations equipped with sophisticated prop traders can also sell rewards and buy them back when price drops below cost-of-production, or use a combination of financial instruments such as collateralized lending, or Bitcoin futures, to protect downside risks. We will cover this topic in greater depth in a future article on hashpower financialization and risk management.

Summary of the hashpower asset class:

In Part II, we will describe the internal logics of the variables that drive the trends in mining, and present how reflexivity plays out in the hashpower market. We will break down the cyclic macro patterns that emerge from these intricate interactions, and use real market examples to illustrate their ebbs and flows.