The Alchemy of Hashpower, Part II.

September 15, 2020

“When events have thinking participants, the subject matter is no longer confined to facts but also includes the participants' perceptions. The chain of causation does not lead directly from fact to fact but from fact to perception and from perception to fact.”

-George Soros, The Alchemy of Finance

In Part I of this series, we presented a simple heuristic for understanding hashpower as an asset class. In mining, everything is connected. To establish a comprehensive understanding of the market dynamic, we need to scrutinize the interactions between the underlying forces in greater depth.

In this article, we start by breaking the mining market cycle into four archetypal stages, each with distinct price trends, hardware capacity, and sentiments. We examine the driving forces in each scenario, and illustrate the roles that the hardware reaction time, and reflexivity in hashpower play in shaping these macro cycles.

Through a series of case studies and theoretical arguments, we intend to introduce a guiding framework for understanding different investment environments in mining. As a coda, we discuss the rising significance of fees in mining calculation. The new opportunities around the fees market, and how fees as a principal variable profoundly changes the hashpower market dynamic.

The Cycles of Mining

The hashpower market dynamics is driven by a convoluted interplay of exogenous and endogenous factors such as price trends, hashpower reflexivity, hardware reaction time, and fees. While the logic that connects them may seem rather straightforward, the unpredictability of each of the variables makes it challenging to produce timeless generalizations.

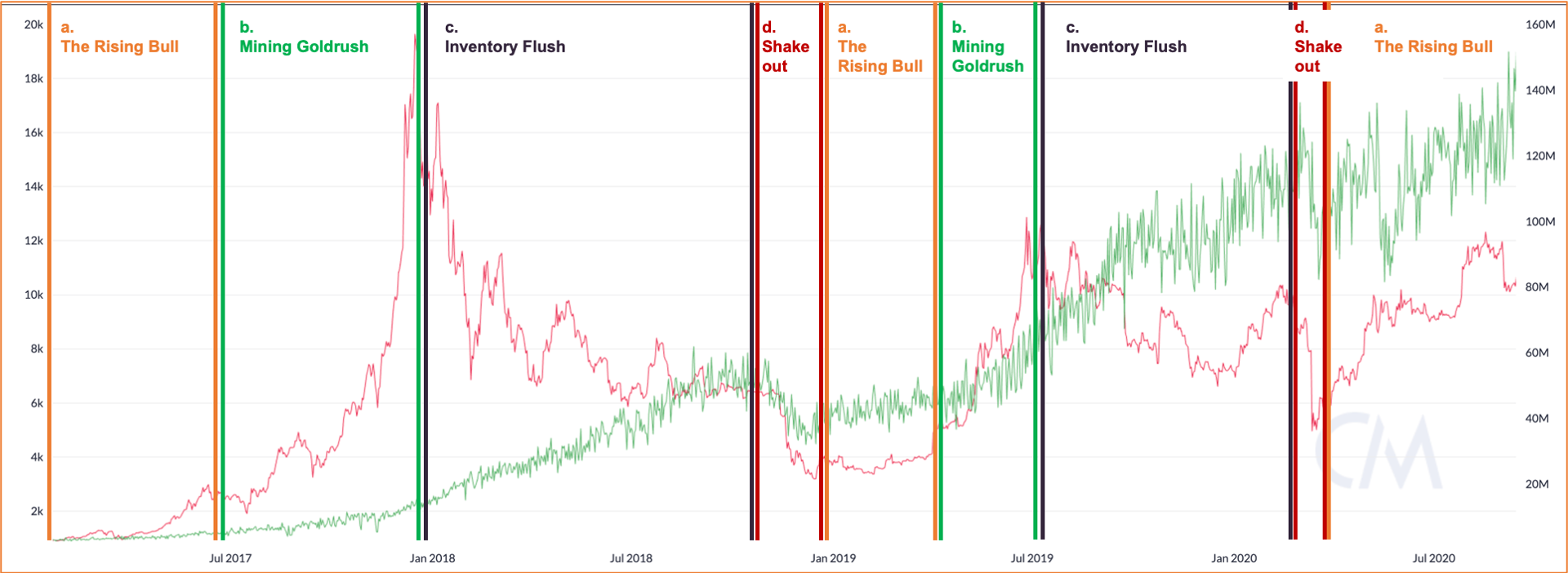

As a result, sometimes the macro patterns emerged may not make any sense, as if price and hashpower live in completely different frames of references. Nevertheless, miners’ actual profitability can be traced. Based on how the market’s impact on historical Bitcoin mining revenue evolves, we can identify four archetypal stages in the mining boom-bust cycle:

(Source: Bitcoin, CoinMetrics)

The cycle is characterized by the vectors of price and network hashpower moving in different directions at different rates. Based on the specs of a Antminer S19 Pro, we can illustrate how its mining revenue change in each scenario:

The Rising Bull

Price outpaces global hashrate growth rate

Mining is the most profitable when difficulty significantly lags the price rally. The “Rising Bull” phase usually happens after long periods where volatility is relatively muted, and the price just begins building momentum while the rest of the market is still uncertain which direction it is going next. Hashpower grows much slower than the price. The increase in hashpower primarily attributed to miners that strongly expect price will rally, or those with access to extremely cheap power sources. For example, between January to April 2019, Bitcoin price was suppressed after the BCH-BSV “Hashpower War” that took place around the same time as the China dry season. Resourceful miners acquired cheap used machines that were trading cheap on the secondary market. Some were also able to capture the opportunity through synthetic mining contracts or cloud mining.

Sometimes exogenous factors can even cause hashpower to drop despite an upward trend in price. Often has to do with physical conditions such as extreme weather flooding that force large data centers to go offline. The flood during the rainy season in Sichuan in 2020 is particularly disastrous. However, these are temporarily setbacks that usually recover overtime.

Another special situation that can force hashpower to decline is hard-fork. After the first Bitmain ASICs were announced, Monero devs decided to switch hashing algorithms once every six months. Every time the network changes the algorithm, a portion of the network hashpower would drop. The developer-initiated hard forks is not just a phenomenon in anti-ASIC projects. The Sia devs embrace ASICs, but they proceeded to hard fork in order to brick specifically Bitmain and Canaan ASICs.

(Source: Monero, CoinMetrics)

The special situations may temporarily halt the hashpower increase, but as the overall upward trend continues, the participants’ positive bias gets reinforced, demand for hashpower increases.

Mining Gold Rush

Price growth rate high, hashpower growth picking up

Once the bull formation has been validated, people are much more eager to purchase machines. New machines are sold out almost right away. Large miners place handsome orders at manufacturers to have their shipment prioritized. In Part I., we described how machines are loosely priced based on static-days-to-breakeven. The shorter the time it takes to breakeven, the more expensive the sellers get to price the machines. Coin price rapidly rallies, demand for new machines follows, but hashrate growth hasn’t picked up the speed yet. These are the windows that manufacturers rake in astronomic profits. Both machine secondary market and cloud mining markets trade at a premium.

This is the same for both ASIC and GPU mining. From 2016 to late 2017, AMD and Nvidia benefited greatly from the meteoric rise of Ethereum. Miners were willing to pay top dollar to get their hands on every GPU available. At one point, the supply shortage was so severe that Nvidia even considered asking retailers to limit sales to 2 per customer. In today’s market, as DeFi brings attention to Ethereum again, manufacturers are racing to produce ETH ASICs.

The hype easily creates FOMO among miners. The positive bias continues to self-reinforce and the expectation rises even faster. Younger altcoin networks going through this phase for the first time may start to attract the attention of ASIC manufacturers.

In early 2019, rumors about hundreds of millions of investments in Grin spread like wildfire. Venture capitals rushed to fund special-purpose vehicles to procure and operate GPU miners. Difficulty skyrocketed not long after the project launched on mainnet, and manufacturers such as Innosilicon and Obelisk were racing to build the first ASIC. The rest is history, the project never lived up to the hype and the ASICs never filled enough order to get produced.

Inventory-flush

Price drops, hashpower growth rate still high

As Howard Marks says, “Everything that produces unusual profitability will attract incremental capital until it becomes overcrowded.” The most destructive effect of a reverting bull market is the Inventory flush.

It is a common occurrence after bull runs and manufacturers overproduce machines. In 2017, manufacturers such as Bitmain misjudged the length of the bull market, and produced an excessive amount of machines throughout 2018. They had to flush out their inventory by gradually lowering the machine prices. In order to get rid of excess chips, Bitmain even rolled out undesirable products such as mining home Wifi routers. As a result, despite the price drop, hashrate continued to climb for several months until profit margin became sufficiently squeezed.

During the same period, many GPU farms became unprofitable due to exponentially-growing hashpower competition, altcoin ASICs (Dash, Zcash etc.) were released into the market while the altcoin prices fell off a cliff. The bear market hit the hardware supply chain so fast that they barely had any time to react. Nvidia posted "disappointing" financial results, and the founder Jen-Hsun Huang went from: “crypto will be an important driver to our business” during the peak of 2017 to: “Can we all please — I don’t want anybody buying cryptocurrencies, okay? Stop it. Enough already. Or buy Bitcoin, don’t buy Ethereum.”

Inventory flush due to overproduction happens in many markets that suffer from high reaction delay. For example, around ten years ago New York City luxury apartments had an epic bull market thanks to generous international buyers. Developers rushed to start new projects. In recent years, the buying power dried up due to various reasons such as currency control, but those new luxury apartments are just becoming available for the market. As a result, developers are stuck with empty buildings.

The Shakeout

Price drops, hashpower drops

Occasionally, mining revenue drops below a threshold where it becomes unprofitable for miners to keep them on. Chinese miners call it the “shut-off price”. In a traditional market, when a correction sets in, negative bias may snowball into a downturn trend. But since hashpower is self-referential, the more hashpower leaves the market, the more “concentrated” remaining hashpower gets.

That’s why in Bitcoin, these over-corrections tend to be ephemeral. In Bitcoin, the threshold is buffered by miners’ expectation of the future mining revenue. They believe the chance to recover is high, hence they are willing to mine at-loss or even deploy more machines while the market goes through the Shakeout. On the other hand in networks infested with speculative miners, such capitulations happen frequently

Things that perform poorly for too long eventually become cheap and attractive. The same cycle will repeat again and again due to, what John Kenneth Galbraith calls, “the extreme brevity of financial memory.”

Plato’s Allegory of Market Fundamentals

Why does the hashpower market manifest these cycles? Intuitively hashrate growth and price trends are connected. How come changes in price don’t lead to commensurate adjustments in hashpower? In other words, why isn’t the hashpower market efficient?

Conceptually, the market is an information-aggregation device that alchemises participants’ perceptions into price information. The faster the price absorbs new information, the more efficient the market is. In a theoretical equilibrium state, the network difficulty should converge to a level where the majority of the miners are operating close to breakeven.

In an early BitcoinTalk post, Satoshi wrote, “The price of any commodity tends to gravitate toward the production cost. If the price is below cost, then production slows down. If the price is above cost, profit can be made by generating and selling more. At the same time, the increased production would increase the difficulty, pushing the cost of generating towards the price.”

However, the Bitcoin market today is far from a passive reflection of its production cost. It’s rare to observe the type of equilibrium that Satoshi envisioned.

While for most physical commodities, the supply is largely determined by production and demand by consumption, speculation pushes the crypto investors to make decisions based on expectation of future price rather than the current supply and demand curves. Thus, the snapshot calculation of mining cost-basis provides very little insight about the market.

Market participants always bring their own biases when processing new information. It’s similar to guessing the shape of a high-dimensional object by examining its projection on a surface in lower-dimension. This is Plato’s Allegory of Cave for the market fundamentals.

With cognitive fallibility comes reflexivity. Reflexivity is an iterative process: The market, a melting pot of biased perceptions, is always flawed in representing reality. As investors make bets on the market, the changes in prices begin to influence the market fundamentals (e.g. companies become more or less capitalized), which in turn affect the price, thus forming a reflexive feedback loop.

Rather than focusing on the hypothetical outcome, it’s more practical to study the process of the change. Reflexivity theory has gained mainstream popularity over the years. Its patterns have been widely observed in equities, currencies, crypto, and even the mining markets.

Reflexivity in Hashpower

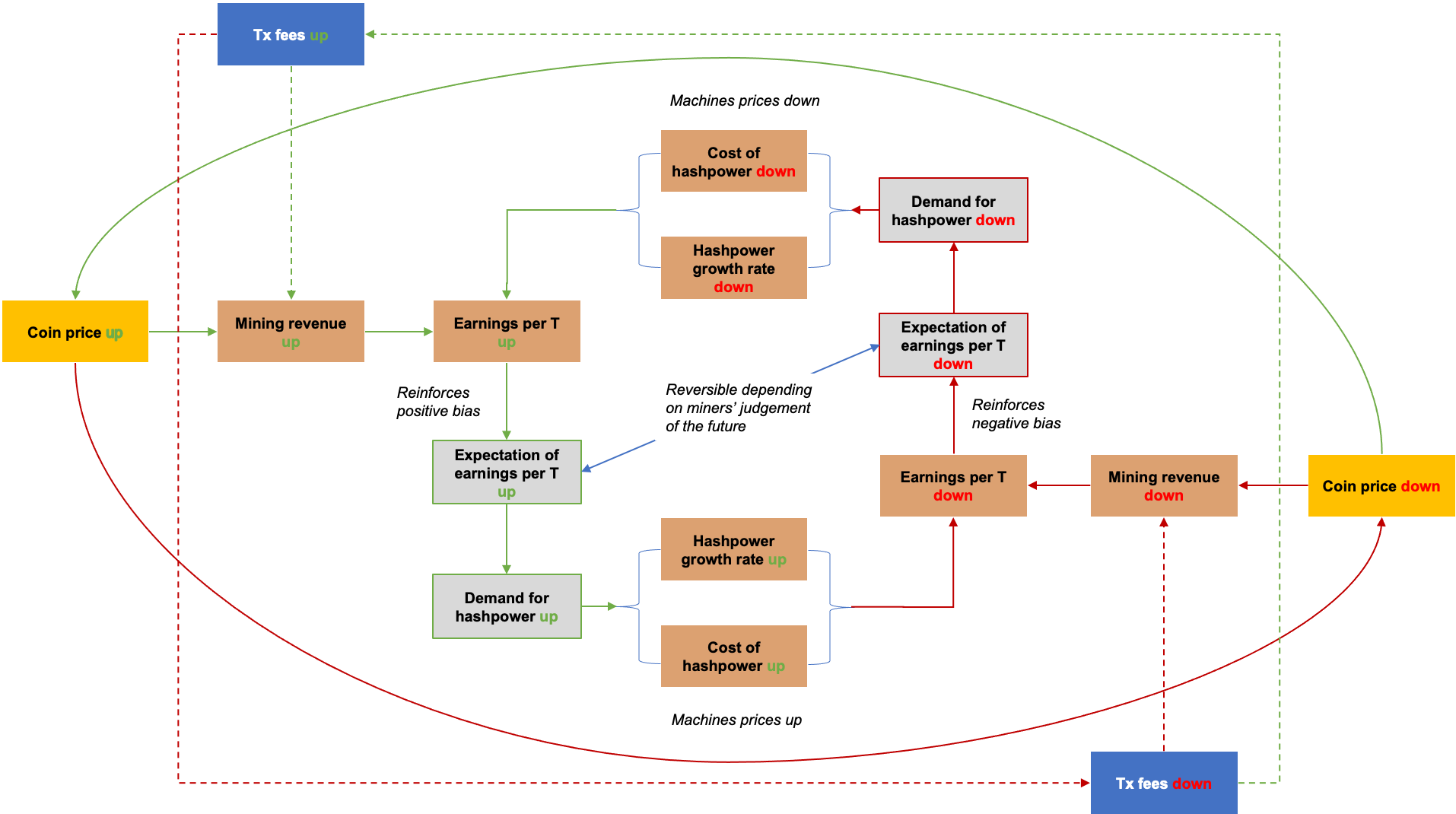

How does reflexivity work in the hashpower market?

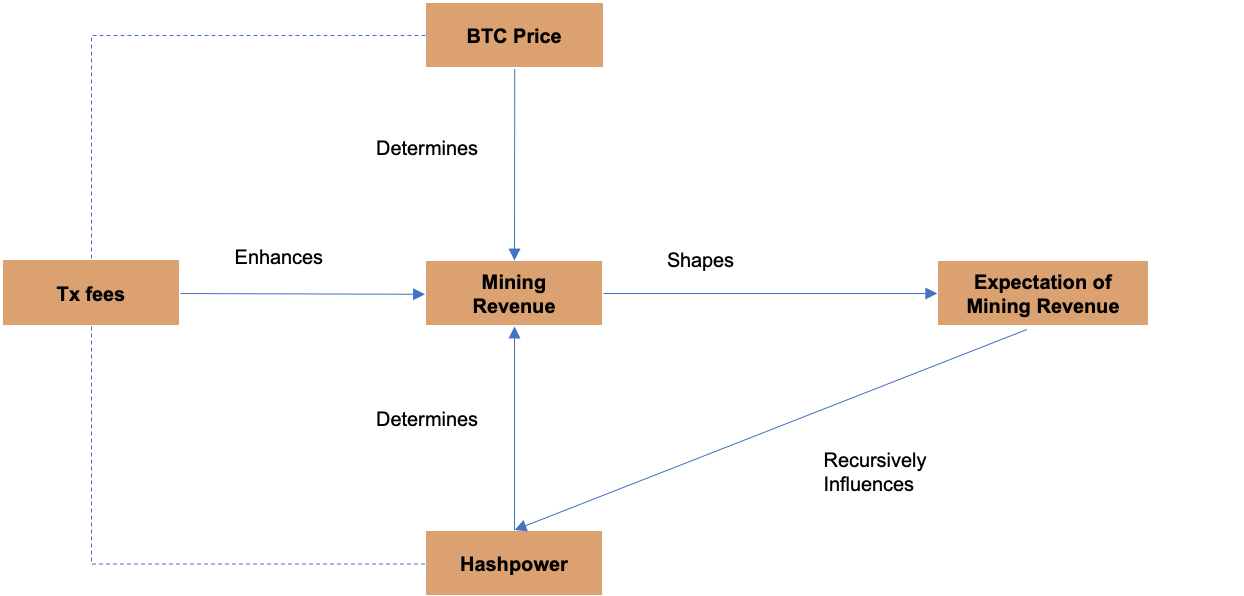

It’s no secret that the demand for hashpower is driven by the value of the coins it produces. Buy and sell decisions are based on the participant’s own expectation of the future mining revenue. Equity investors set their expectation of future price by performing macro, industry, and company analysis. Hashpower investors set their expectation of the future mining revenue by assessing trends in price, fees, and network hashrate growth.

Everyone has their own (often flawed) heuristic for setting expectations for price trends. Hashrate growth, on the other hand, is much more challenging to build models for. One reason is that it’s dynamically recursive: the more hashpower floods the market the more diluted each unit becomes. Changes lead to adjustments in expectations, and thus it recursively influences the current mining revenue. Every participant in the hashpower market constantly changes the rest of the market.

This means the most scientific way to predict hashrate growth is by collecting sales numbers from manufacturers, large miners, service providers, and distributors. But the mining machine business is plagued with recondite information. It takes Herculean effort to acquire accurate and updated data. Since it is difficult to reliably set expectations for hashrate growth, and income from fees is still eclipsed by block rewards, naturally expectation for future price becomes the de facto driver. After all, why would anyone spend so much capital and energy getting involved in mining if the person is not optimistic about the future price?

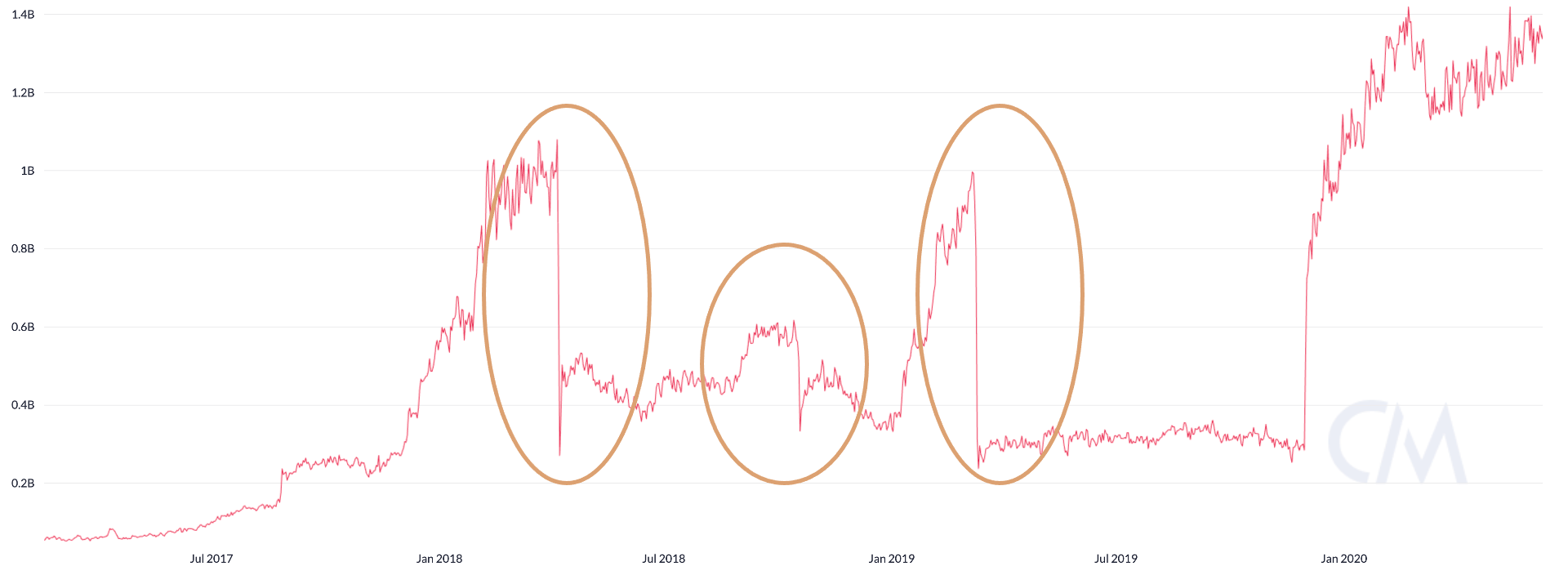

Gathering mining data is an onerous task, but is it possible to untangle the dependence structure between price trend and hashrate growth?

We often see divergences in hashpower and price as illustrated in the four stages of the market. Information in capital markets travels fast. Hardware manufacturing & transportation is slow. The hashpower market is the opposite of what’s idealized in Efficient Market Hypothesis. This renders vanilla correlation analysis useless. We need to interrogate the data at different time scales.

In a comprehensive research report published by BitOoda, they analyzed the price & hashrate changes in 2019, and discovered that it took around an average of 4-6 months before hashrate started following the price rally.

Note that this lag time is not fixed. Depending on the production capacity and availability on secondary markets, the lag time varies for each market move. Different networks also have different response times.

Take Litcoin for example, between Jan-May 2018 its hashrate took a long time to respond to the price change. After July, hashpower and price became very synchronized.

(Source: Litecoin, CoinMetrics)

Extending the analysis to Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Litecoin over a longer period to 2017-2020, we discovered that the average response times are 60-120 days, 30-60 days, and 15 days respectively.

Process:

Aggregate data into periods of 15 days:

Columns in the dataset are Date (15 days ending), mean Price over 15 days, mean hash rate over 15 days

For each 15 day period, calculate:

% change in price after 15 days, 30 days, 45 days, …, 180 days

% change in hashrate after 15 days, 30 days, 45 days, …, 180 days

Compute correlation between price change and hashrate change over different time periods

Read the matrix as: correlation between price change over ‘y’ days and change in hashrate after a period of ‘y’ days (following the x-days period that saw a change in price)

In the future, we intend to examine how the response time evolves over time, and anatomize the underlying driving forces. Our next project is to quantify the endogeneity of the hashpower market, and build an index to measure reflexivity in various networks.

The responsiveness is neither inherently good or bad. It is a function of the availability of the hashpower on the market at the given time. Some smaller networks dominated by general-purpose hardwares on average have much shorter response time. Their hashpower responds to price ups and downs faster because the miners on these networks are less loyal. Compared to ASIC miners, they can easily switch to a different network when profitable. Some mining pools offer automatic switching services that constantly hops over several different networks to maximize profit (known as “Profit Switchers”, or “Machine-gun Pools”).

Note that a network dominated by ASICs doesn’t necessarily make it Value-Driven (e.g. Litecoin post 2019); and a network dominated by GPUs are not entirely Speculative (e.g. Ethereum). That is determined by the project itself and its community.

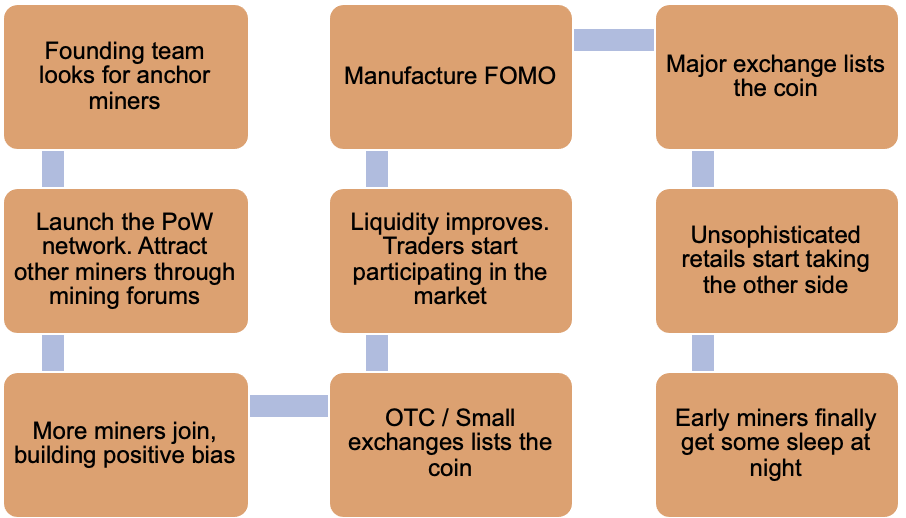

In most cases changes in price precedes changes in hashpower. Occasionally we can observe the inverse in altcoin markets, usually altcoins that are about to go through Halving or special market events. The Halving is one of the biggest recurring self-fulling prophecies in cryptocurrency, and expectations of a post-Halving rally drives miners to deploy new machines to mine on the network ahead of time. Sometimes coordinated pump & dump groups would deploy hashrate to accumulate enough coins before pushing up the price for the ultimate reap.

This game is also common among the GPU miners speculating on new projects. Upon launch, most coins are traded exclusively on OTC markets with terrible liquidity. Miners don't have good channels to exit their positions as they continue to operate at a loss until community development gains momentum. As the community grows, bigger exchanges will list the coin, giving early miners a chance to take some profits.

This does not imply the hashpower increase will cause the price to increase. It’s a high risk bet and there are a myriad of examples of failures. Many stars need to align in order for such a heist to work out favorably. It can go sideway in every step of the process below:

GPU-launch was popular between 2017 and early 2019. Some analysts suggested that proof-of-work may be a fairer launch model than ICOs that issue SAFTs to venture capitals. What constitutes a fair launch is a much broader topic. It’s a controversial subject even among DeFi projects that have nothing to do with proof-of-work. The launch method and the hashpower acquired do not guarantee price rally in the future. In essence it is a varied form of ICO with a higher barrier of entry, the same casino game of throwing darts in the dark.

The hardware reaction time, regardless of the length, is a source of endogeneity. This means that when modeling the impact of price on hashrate growth (or vice versa), the impact is likely underestimated or overestimated. Hence decisions based on inferences from the model could be disastrous as an input to investment decisions.

The moral of the story is that the connection does not imply a causal relation between hashpower and price. One does not mechanically induce the other. It is the expectation of future mining revenue and the expectation of hashpower growth that are continuously reinforcing each other.

The Rising Significance of Fees

To take the macro model at the beginning of the article one step further, fee trend should be a principal variable as well. As discussed, at the moment the expectation of mining revenue is primarily driven by price trends. In the past August, Ethereum miners made a total of $113 million in profit. The previous all-time high ($64 million) was reported in January 2018. The exorbitant fees is explainable in light of the rising on-chain traffics from the DeFi projects.

Having transaction fees as a key variable opens possibilities for new games. For instance, arbitrage opportunities on Ethereum-based decentralized exchanges incentivize competing bots to bid up transaction fees in priority gas auctions. Miners who have control over the ordering of transactions can take advantage of these auctions via ordering optimization fees. This is part of a broader topic called miner-extractable value (MEV), that is the value that miners can earn directly from smart contracts. There will be more services and infrastructures (such as Sparkpool’s Taichi network, which improves transaction broadcast) that tackle various aspects of the emerging fees market.

As fee income constitutes a growing portion of the mining revenue, it adds another dimension to mining revenue calculations. Both the expectation of price and the expectation of fees will influence the expectation of future mining revenue:

The reflexivity theory is a useful heuristic for understanding the ebb and flow. However, the model cannot replace understanding the fundamental vulnerabilities in the hashpower market. As the mining industry becomes more industrialized, the capital expenditure inevitably grows. Meanwhile, fees as % mining revenue increases, and the four archetypal stages will expand to even more complex scenarios. The combined effect will introduce more challenges and uncertainties to cash flow management.

After a decade of development, the hashpower capital markets still suffer from the lack of standard terms and pricing heuristics. The industry demands proper risk management practices and mature market mechanisms to secure continuous long-term investments into hashpower.

In the next article, we will discuss in-depth on risk management framework, creative financing & hedging strategies, as well as the long-term impact of financialization to the mining industry.